Every day we creep a little closer to Douglas Adams’ famous and prescient babel fish. A new research project from Google takes spoken sentences in one language and outputs spoken words in another — but unlike most translation techniques, it uses no intermediate text, working solely with the audio. This makes it quick, but more importantly lets it more easily reflect the cadence and tone of the speaker’s voice.

Translatotron, as the project is called, is the culmination of several years of related work, though it’s still very much an experiment. Google’s researchers, and others, have been looking into the possibility of direct speech-to-speech translation for years, but only recently have those efforts borne fruit worth harvesting.

Translating speech is usually done by breaking down the problem into smaller sequential ones: turning the source speech into text (speech-to-text, or STT), turning text in one language into text in another (machine translation), and then turning the resulting text back into speech (text-to-speech, or TTS). This works quite well, really, but it isn’t perfect; Each step has types of errors it is prone to, and these can compound one another.

Furthermore, it’s not really how multilingual people translate in their own heads, as testimony about their own thought processes suggests. How exactly it works is impossible to say with certainty, but few would say that they break down the text and visualize it changing to a new language, then read the new text. Human cognition is frequently a guide for how to advance machine learning algorithms.

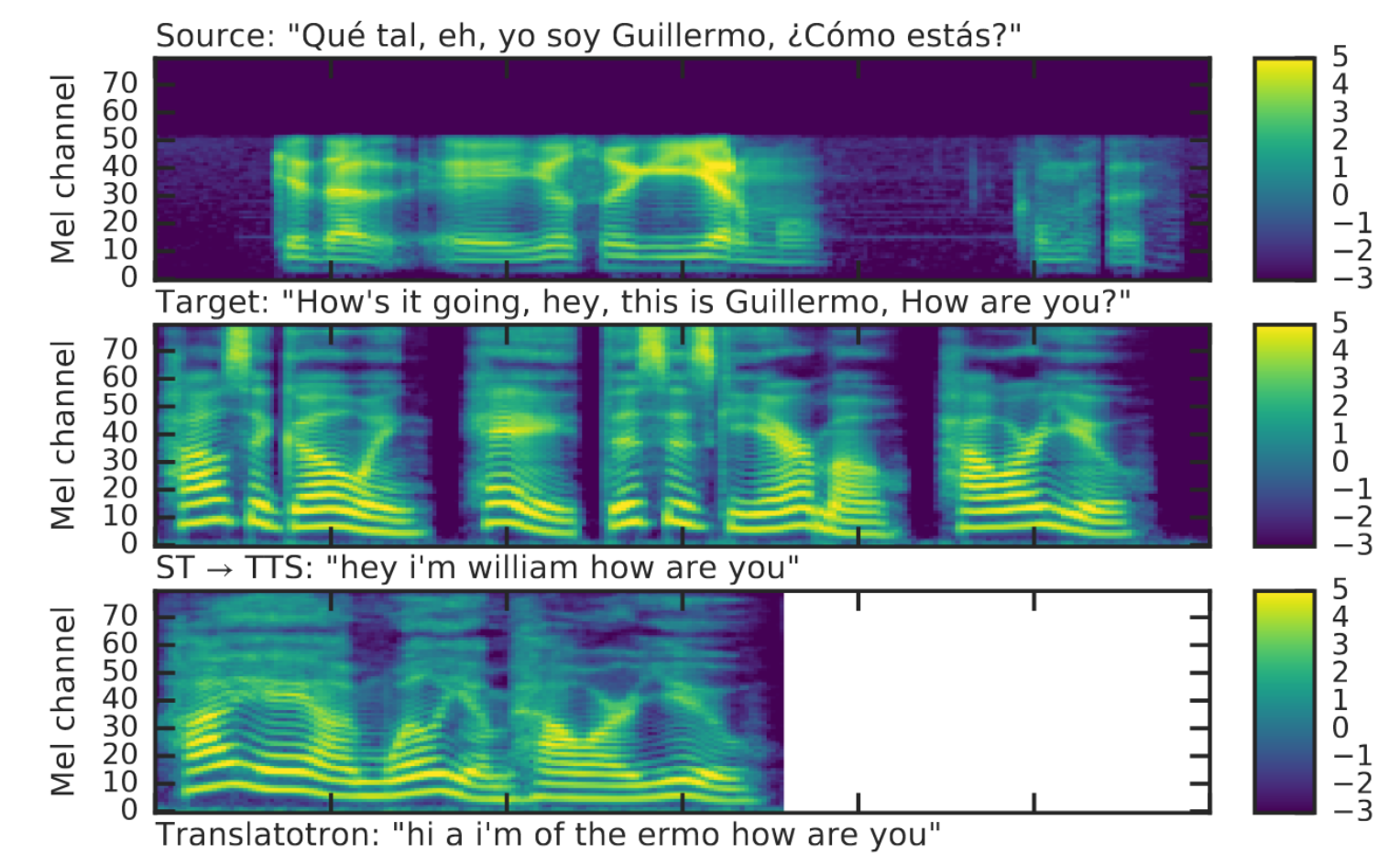

Spectrograms of source and translated speech. The translation, let us admit, is not the best. But it sounds better!

To that end researchers began looking into converting spectrograms, detailed frequency breakdowns of audio, of speech in one language directly to spectrograms in another. This is a very different process from the three-step one, and has its own weaknesses, but it also has advantages.

One is that, while complex, it is essentially a single-step process rather than multi-step, which means, assuming you have enough processing power, Translatotron could work quicker. But more importantly for many, the process makes it easy to retain the character of the source voice, so the translation doesn’t come out robotically, but with the tone and cadence of the original sentence.

Naturally this has a huge impact on expression and someone who relies on translation or voice synthesis regularly will appreciate that not only what they say comes through, but how they say it. It’s hard to overstate how important this is for regular users of synthetic speech.

The accuracy of the translation, the researchers admit, is not as good as the traditional systems, which have had more time to hone their accuracy. But many of the resulting translations are (at least partially) quite good, and being able to include expression is too great an advantage to pass up. In the end, the team modestly describes their work as a starting point demonstrating the feasibility of the approach, though it’s easy to see that it is also a major step forward in an important domain.

The paper describing the new technique was published on Arxiv, and you can browse samples of speech, from source to traditional translation to Translatotron, at this page. Just be aware that these are not all selected for the quality of their translation, but serve more as examples of how the system retains expression while getting the gist of the meaning.

0 Comments

Post a Comment