Over 2 million women were diagnosed with breast cancer in 2018. And while the diagnosis doesn’t have to be a death sentence for women in countries like the United States, in developing countries three times as many women die from the disease.

Breast cancer survival rates range from 80% or over in North America, Sweden and Japan to around 60% in middle-income countries and below 40% in low-income countries, according to data provided the World Health Organization.

And the WHO blames these low survival rates in less developed countries on the lack of early detection programs, which result in a higher proporation of women presenting with late-stage disease. The problem is exacerbated by a lack of adequate diagnostic technologies and treatment facilities, according to the WHO.

A group of Johns Hopkins University undergraduates believe they have found a solution. The four women, none of whom are over 21-years-old, have developed a new, low-cost, disposable core needle biopsy technology for physicians and nurses that could dramatically reduce cost and waste, thereby increasing the availability of screening technologies in emerging markets.

They’ve taken the technology they developed at Johns Hopkins University and created a new startup called Ithemba, which means “hope” in Swahili, to commercialize their device. While the company is still in its early days, the women recently won the undergraduate Lemelson-MIT Student Prize competition, and has received $60,000 in non-dilutive grant funding and a $10,000 prize associated with the Lemelson award.

Students at Johns Hopkins had been working through the problem of developing low-cost diagnostic tools for breast cancer for the past three years, spurred on by Dr. Susan Harvey, the head of Johns Hopkins Section of Breast Imaging.

While Dr. Harvey presented the problem, and several students tried to tackle it, Ithemba’s co-founders — the biomedical engineering undergrads Laura Hinson, Madeline Lee, Sophia Triantis, and Valerie Zawicki — were the first to bring a solution to market.

Ithemba co-founders Laura Hinson, Madeline Lee, Valerie Zawicki and Sophia Triantis

The 21-year-old Zawicki, who grew up in Long Beach, Calif., has a personal connection to the work the team is doing. When she was just five years old her mother was diagnosed with breast cancer, and the cost of treatment and toll it took on the family forced the family to separate. “My sister moved in with my grandparents,” Zawicki says, while her mother underwent treatment. “When I came to college I was looking for a way to make an impact in the healthcare space and was really inspired by the care my mom received.”

The same is true for Zawicki’s co-founder, Triantis.

“We have an opportunity to solve problems that really need solving,” says Triantis, a 20-year-old undergraduate. “Breast cancer has affected so many people close to me… It is the most common cancer among women [and] the fact that women in low resource settings do not have the same standard of diagnostic care really inspired me to work on a solution.”

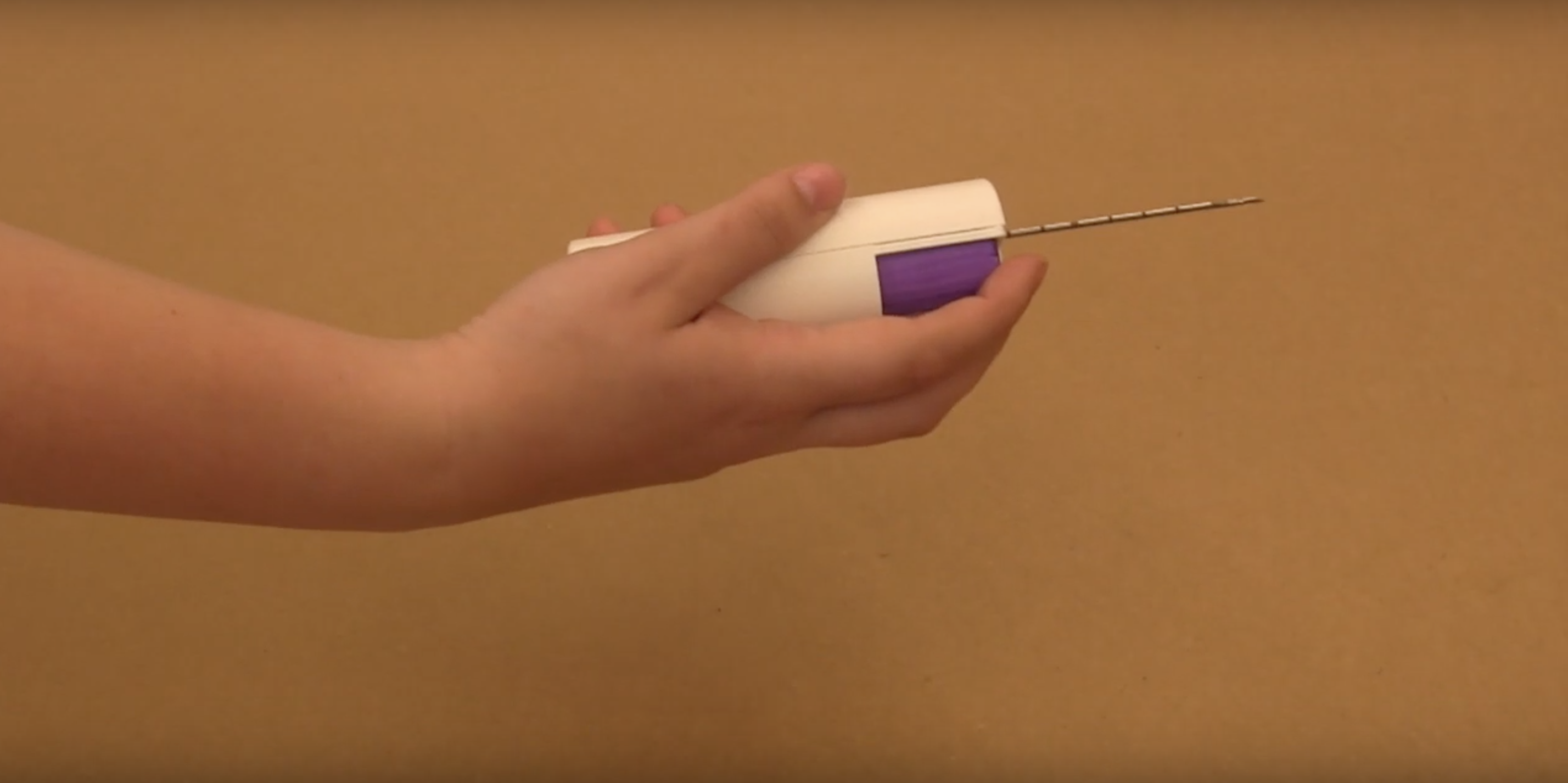

What the four women have made is a version of a core-needled biopsy that has a lower risk of contamination than the reusable devices that are currently on the market and is cheaper than the expensive disposable needles that are the only other option, the founders say.

“We’ve designed a novel, disposable portion that attaches to the reusable device and the disposable portion has an ability to trap contaminants that would come back through the needle into the device,” says Triantis. “What we’ve created is a way to trap that and have that full portion be disposable and making the device as easy to clean as possible… with a bleach wipe.”

Ithemba’s low-cost reusable core-needle biopsy device

The company is currently in the process of doing benchtop tests on the device, and will look to file a 510K to be certified as a Class 2 medical device. Already a clinic in South Africa and a hospital in Peru are on board as early customers for the new biopsy tool.

At the heart of the new tool is a mechanism which prevents blood from being drawn back into a needle. The team argues it makes reusable needles much less susceptible to contamination and can replace the disposable needles that are too expensive for many emerging market clinics and hospitals.

Zawicki had been working on the problem for a while when Hinson, Lee, and Triantis joined up. “I joined the team when the problem was presented,” says Zawicki. “The project began with this problem that was pitched three years ago, but the four of us are really those that have brought this to life in terms of a device.”

Crucially for the team, Johns Hopkins was fully supportive of the women taking their intellectual property and owning it themselves. “We received written approval from the tech transfer office to file independently,” says Zawicki. “That is really unique.”

Coupled with the Lemelson award, Ithemba sees a clear path to ownership of the intellectual property and is filing patents on its device.

Zawicki says that it could be anywhere from three to five years before the device makes it on to the market, but there’s the potential for partnerships with big companies in the biopsy space that could accelerate that time to market.

“Once we get that process solidified and finalize our design we will wrap up our benchtop testing so we can move toward clinical trials by next summer, in 2020,” Zawicki says.

0 Comments

Post a Comment