We all rely on maps to get where we’re going or investigate a neighborhood for potential brunch places, but the data we’re looking at is often old, vague, or both. Nexar, maker of dashcam apps and cameras, aims to put fresh and specific data on your map with images from the street taken only minutes before.

If you’re familiar with dash cams, and you’re familiar with Google’s Street View, then you can probably already picture what Live Map essentially is. It’s not quite as easy to picture how it works or why it’s useful.

Nexar sells dash cams and offers an app that turns your phone into one temporarily, and the business has been doing well, with thousands of active users on the streets of major cities at any given time. Each node of this network of gadgets shares information with the other nodes — warning of traffic snarls, potholes, construction, and so on.

The team saw the community they’d enabled trading videos and sharing data derived by automatic analysis of their imagery, and, according to co-founder and CTO Bruno Fernandez-Ruiz, asked themselves: Why shouldn’t this data shouldn’t be available to the public as well?

Actually there are a few reasons — privacy chief among them. Google has shown that properly handled, this kind of imagery can be useful and only minimally invasive. But knowing where someone or some car was a year or two ago is one thing; knowing where they were five minutes ago is another entirely.

Fortunately, from what I’ve heard, this issue was front of mind for the team from the start. But it helps to see what the product looks like in action before addressing that.

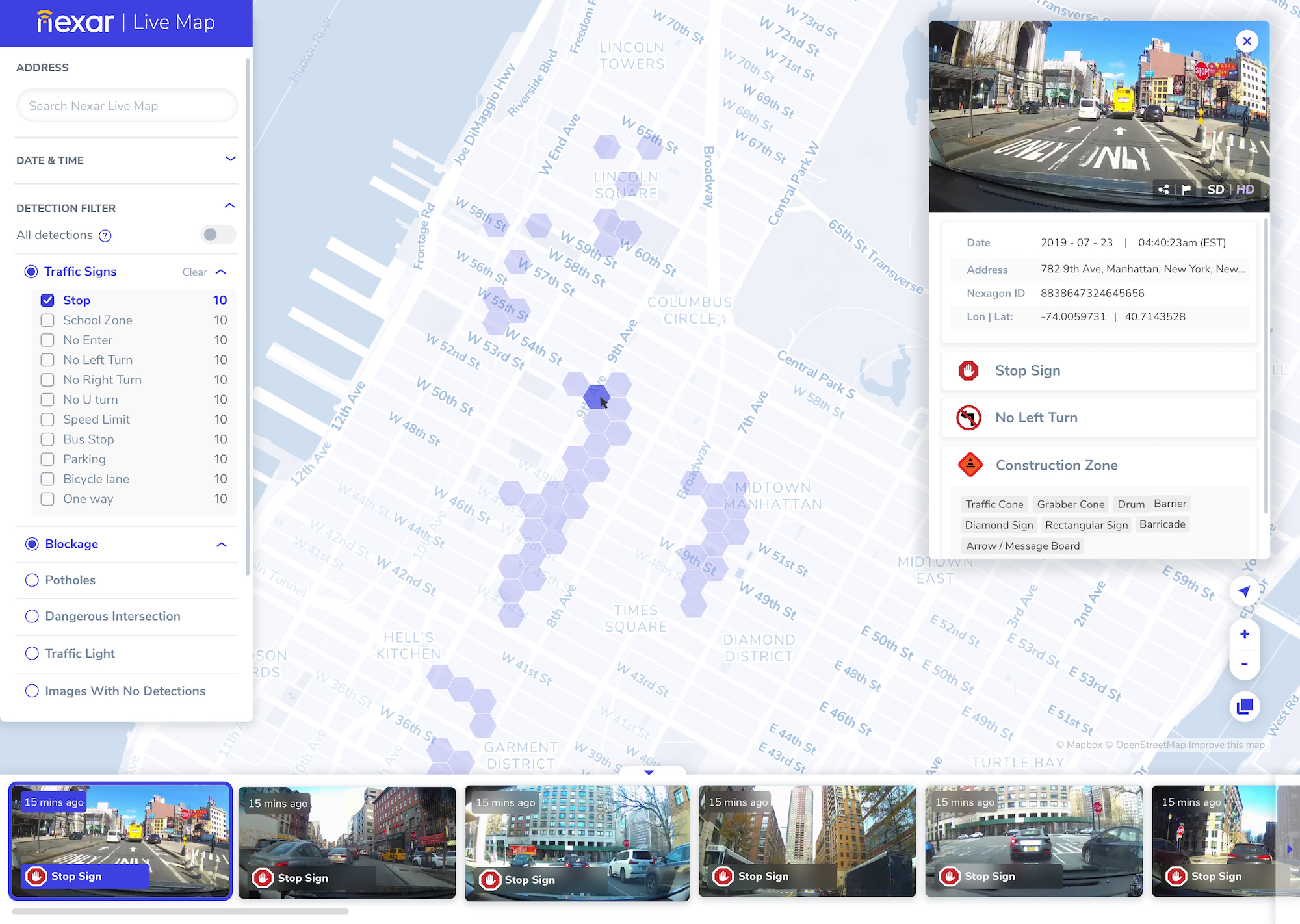

Zooming in on a hexagonal map section, which the company has dubbed “nexagons,” polls the service to find everything the service knows about that area. And the nature of the data makes for extremely granular information. Where something like Google Maps or Waze may say that there’s an accident at this intersection, or construction causing traffic, Nexar’s map will show the locations of the orange cones to within a few feet, or how far into the lanes that fender-bender protrudes.

You can also select the time of day, letting you rewind a few minutes or a few days — what was it like during that parade? Or after the game? Are there a lot of people there late at night? And so on.

Right now it’s limited to a web interface, and to New York City — the company has enough data to launch in several other areas in the U.S. but wants to do a slower roll-out to identify issues and opportunities. An API is on the way as well. (Europe, unfortunately, may be waiting a while, though the company says it’s GDPR-compliant.)

The service uses computer vision algorithms to identify a number of features, including signs (permanent and temporary), obstructions, even the status of traffic lights. This all goes into the database, which gets updated any time a car with a Nexar node goes by. Naturally it’s not in 360 and high definition — these are forward-facing cameras with decent but not impressive resolution. It’s for telling what’s in the road, not for zooming in to spot a street address.

Of course, construction signs and traffic jams aren’t the only things on the road. As mentioned before it’s a serious question of privacy to have constantly updating, public-facing imagery of every major street of a major city. Setting aside the greater argument of the right to privacy in public places and attendant philosophical problems, it’s simply the ethical thing to do to minimize how much you expose people who don’t know they’re being photographed.

To that end Nexar’s systems carefully detect and blur out faces before any images are exposed to public view. License plates are likewise obscured so that neither cars nor people can be easily tracked from image to image. Of course one may say that here is a small red car that was on 4th, and is on 5th a minute later — probably the same. But systematic surveillance rather than incidental is far easier with an identifier like a license plate.

In addition to protecting bystanders, Nexar has to think of the fact that an image from a car by definition places that car in a location at a given time, allowing them to be tracked. And while the community essentially opts into this kind of location and data sharing when they sign up for an account, it would be awkward if the public website let a stranger track a user all the way to their home or watch their movements all day.

“The frames are carefully random to begin with so people can’t be soloed out,” said Fernandez-Ruiz. “We eliminate any frames near your house and your destination.” As far as the blurring, he said that “We have a pretty robust model, on par with anything you can see in the industry. We probably are something north of 97-98 percent accurate for private data.”

So what would you do with this kind of service? There is, of course, something fundamentally compelling about being able to browse your city in something like real time.

On Google, there’s a red line. We show you an actual frame – a car blocking the right lane right there. It gives you a human connection,” said Fernandez-Ruiz. “There’s an element of curiosity about what the world looks like, maybe not something you do every day, but maybe once a week, or when something happens.”

No doubt we are many of us guilty of watching dash-cam footage or even Street View pictures of various events, pranks, and other occurrences. But basic curiosity doesn’t pay the bills. Fortunately there are more compelling use cases.

“One that’s interesting is construction zones. You can see individual elements like cones and barriers – you can see where exactly they are, when they’re started etc. We want to work with municiapl authorities, department of transportation, etc on this — it gives them a lot of information on what their contractors are doing on the road. That’s one use case that we know about and understand.”

In fact there are already some pilot programs in Nevada. And although it’s rather a prosaic application of a 24/7 surveillance apparatus, it seems likely to do some good.

But the government angle brings in an unsavory linen of thinking — what if the police want to get unblurred dash cam footage of a crime that just happened, or one of many such situations where tech’s role has historically been a mixed blessing?

“We’ve given a lot of thought to this, and it this concerns our investors highly,” Fernandez-Ruiz admitted. “There are two things we’ve done. One is we’ve differentiated what data the user owns and what we have. The data they send is theirs – like Dropbox. What we get is these anonymized blurred images. Obviously we will comply with the law, but as far as ethical applications of big data and AI, we’ve said we’re not going to be a tool of an authoritarian government. So we’re putting processes in place — even if we get a subpoena, we can say: This is encrypted data, please ask the user.”

That’s some consolation, but it seems clear that tools like this one are more a question than an answer. It’s an experiment by a successful company and may morph into something ubiquitous and useful or a niche product used by professional drivers and municipal governments. But in tech, if you have the data, you use it. Because if you don’t, someone else will.

You can test out Nexar’s Live Map here.

0 Comments

Post a Comment