The online campaigning activities of the UK’s new prime minister, Boris Johnson, have already caught the eye of the country’s data protection watchdog.

Responding to concerns about the scope of data processing set out in the Conservative Party’s Privacy Policy being flagged to it by a Twitter user, the Information Commissioner’s Office replied that: “This is something we are aware of and we are making enquiries.”

The Privacy Policy is currently being attached to an online call to action that ask Brits to tell the party what the most “important issue” to them and their family is, alongside submitting their personal data.

Anyone sending their contact details to the party is also asked to pick from a pre-populated list of 18 issues the three most important to them. The list runs the gamut from the National Health Service to brexit, terrorism, the environment, housing, racism and animal welfare, to name a few. The online form also asks responders to select from a list how they voted at the last General Election — to help make the results “representative”. A final question asks which party they would vote for if a General Election were called today.

Speculation is rife in the UK right now that Johnson, who only became PM two weeks ago, is already preparing for a general election. His minority government has been reduced to a majority of just one MP after the party lost a by-election to the Liberal Democrats last week, even as an October 31 brexit-related deadline fast approaches.

People who submit their personal data to the Conservative’s online survey are also asked to share it with friends with “strong views about the issues”, via social sharing buttons for Facebook and Twitter or email.

“By clicking Submit, I agree to the Conservative Party using the information I provide to keep me updated via email, online advertisements and direct mail about the Party’s campaigns and opportunities to get involved,” runs a note under the initial ‘submit — and see more’ button, which also links to the Privacy Policy “for more information”.

If you click through to the Privacy Policy will find a laundry list of examples of types of data the party says it may collect about you — including what it describes as “opinions on topical issues”; “family connections”; “IP address, cookies and other technical information that you may share when you interact with our website”; and “commercially available data – such as consumer, lifestyle, household and behavioural data”.

“We may also collect special categories of information such as: Political Opinions; Voting intentions; Racial or ethnic origin; Religious views,” it further notes, and it goes on to claim its legal basis for processing this type of sensitive data is for supporting and promoting “democratic engagement and our legitimate interest to understand the electorate and identify Conservative supporters”.

Third party sources for acquiring data to feed its political campaigning activity listed in the policy include “social media platforms, where you have made the information public, or you have made the information available in a social media forum run by the Party” and “commercial organisations”, as well as “publicly accessible sources or other public records”.

“We collect data with the intention of using it primarily for political activities,” the policy adds, without specifying examples of what else people’s data might be used for.

It goes on to state that harvested personal data will be combined with other sources of data (including commercially available data) to profile voters — and “make a prediction about your lifestyle and habits”.

This processing will in turn be used to determine whether or not to send a voter campaign materials and, if so, to tailor the messages contained within it.

In a nutshell this is describing social media microtargeting, such as Facebook ads, but for political purposes; a still unregulated practice that the UK’s information commissioner warned a year ago risks undermining trust in democracy.

Last year Elizabeth Denham went so far as to call for an ‘ethical pause’ in the use of microtargeting tools for political campaigning purposes. But, a quick glance at Facebook’s Ad Library Archive — which it launched in response to concerns about the lack of transparency around political ads on its platform, saying it will imprints of ads sent by political parties for up to seven years — the polar opposite has happened.

Since last year’s warning about democratic processes being undermined by big data mining social media platforms, the ICO has also warned that behavioral ad targeting does not comply with European privacy law. (Though it said it will give the industry time to amend its practices rather than step in to protect people’s rights right now.)

Denham has also been calling for a code of conduct to ensure voters understand how and why they’re being targeted with customized political messages, telling a parliamentary committee enquiry investigating online disinformation early last year that the use of such tools “may have got ahead of where the law is” — and that the chain of entities involved in passing around voters’ data for the purposes of profiling is “much too opaque”.

“I think it might be time for a code of conduct so that everybody is on a level playing field and knows what the rules are,” she said in March 2018, adding that the use of analytics and algorithms to make decisions about the microtargeting of voters “might not have transparency and the law behind them.”

The DCMS later urged government to fast-track changes to electoral law to reflect the use of powerful new voter targeting technologies — including calling for a total ban on microtargeting political ads at so-called ‘lookalike’ audiences online.

The government, then led by Theresa May, gave little heed to the committee’s recommendations.

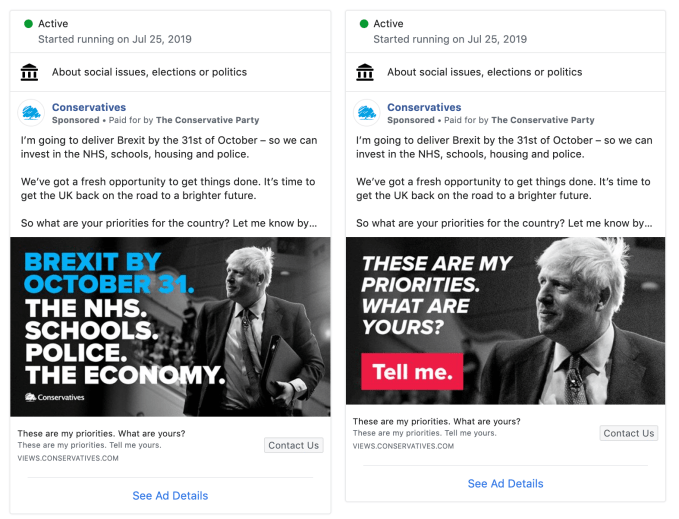

And from the moment he arrived in Number 10 Downing Street last month, after winning a leadership vote of the Conservative Party’s membership, new prime minister Johnson began running scores of Facebook ads to test voter opinion.

Sky News reported that the Conservative Party ran 280 ads on Facebook platforms on the PM’s first full day in office. At the time of writing the party is still ploughing money into Facebook ads, per Facebook’s Ad Library Archive — shelling out £25,270 in the past seven days alone to run 2,464 ads, per Facebook’s Ad Library Report, which makes it by far the biggest UK advertiser by spend for the period.

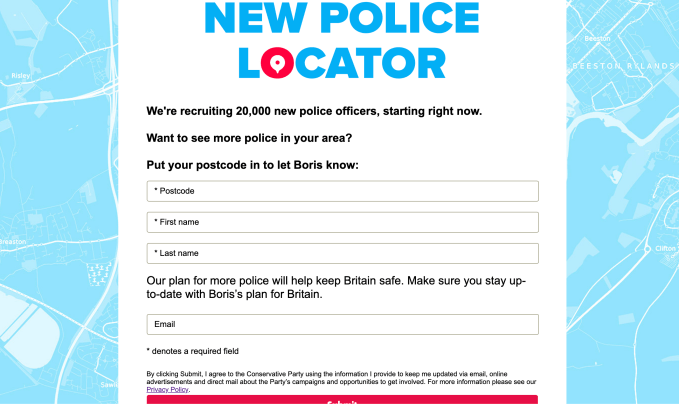

The Tories’ latest crop of Facebook ads contain another call to action — this time regarding a Johnson pledge to put 20,000 more police officers on the streets. Any Facebook users who clicks the embedded link is redirected to a Conservative Party webpage described as a ‘New police locator’, which informs them: “We’re recruiting 20,000 new police officers, starting right now. Want to see more police in your area? Put your postcode in to let Boris know.”

But anyone who inputs their personal data into this online form will also be letting the Conservatives know a lot more about them than just that they want more police on their local beat. In small print the website notes that those clicking submit are also agreeing to the party processing their data for its full suite of campaign purposes — as contained in the expansive terms of its Privacy Policy mentioned above.

So, basically, it’s another data grab…

Political microtargeting was of course core to the online modus operandi of the disgraced political data firm, Cambridge Analytica, which infamously paid an app developer to harvest the personal data of millions of Facebook users back in 2014 without their knowledge or consent — in that case using a quiz app wrapper and Facebook’s lack of any enforcement of its platform terms to grab data on millions of voters.

Cambridge Analytica paid data scientists to turn this cache of social media signals into psychological profiles which they matched to public voter register lists — to try to identify the most persuadable voters in key US swing states and bombard them with political messaging on behalf of their client, Donald Trump.

Much like the Conservative Party is doing, Cambridge Analytica sourced data from commercial partners — in its case claiming to have licensed millions of data points from data broker giants such as Acxiom, Experian, Infogroup. (The Conservatives’ privacy policy does not specify which brokers it pays to acquire voter data.)

Aside from data, what’s key to this type of digital political campaigning is the ability, afforded by Facebook’s ad platform, for advertisers to target messages at what are referred to as ‘lookalike audience’ — and do so cheaply and at vast scale. Essentially, Facebook provides its own pervasive surveillance of the 2.2BN+ users on its platforms as a commercial service, letting advertisers pay to identify and target other people with a similar social media usage profile to those whose contact details they already hold, by uploading their details to Facebook.

This means a political party can data-mine its own supporter base to identify the messages that resonant best with different groups within that base, and then flip all that profiling around — using Facebook to dart ads at people who may never in their life have clicked ‘Submit — and see more‘ on a Tory webpage but who happen to share a similar social media profile to others in the party’s target database.

Facebook users currently have no way of blocking being targeted by political advertisers on Facebook, nor indeed no way to generally switch off microtargeted ads which use personal data to select marketing messages.

That’s the core ethical concern in play when Denham talks about the vital need for voters in a democracy to have transparency and control over what’s done with their personal data. “Without a high level of transparency – and therefore trust amongst citizens that their data is being used appropriately – we are at risk of developing a system of voter surveillance by default,” she warned last year.

However the Conservative Party’s privacy policy sidesteps any concerns about its use of microtargeting, with the breeze claim that: “We have determined that this kind of automation and profiling does not create legal or significant effects for you. Nor does it affect the legal rights that you have over your data.”

The software the party is using for online campaigning appears to be NationBuilder: A campaign management software developed in the US a decade ago — which has also been used by the Trump campaign and by both sides of the 2016 Brexit referendum campaign (to name a few of its many clients).

Its privacy policy shares the same format and much of the same language as one used by the Scottish National Party’s yes campaign during Scotland’s independence reference, for instance. (The SNP was an early user of NationBuilder to link social media campaigning to a new web platform in 2011, before going on to secure a majority in the Scottish parliament.)

So the Conservatives are by no means the only UK political entity to be dipping their hands in the cookie jar of social media data. Although they are the governing party right now.

Indeed, a report by the ICO last fall essentially called out all UK political parties for misusing people’s data.

Issues “of particular concern” the regulator raised in that report were:

- the purchasing of marketing lists and lifestyle information from data brokers without sufficient due diligence around those brokers and the degree to which the data has been properly gathered and consented to;

- a lack of fair processing information;

- the use of third-party data analytics companies with insufficient checks that those companies have obtained correct consents for use of data for that purpose;

- assuming ethnicity and/or age and combining this with electoral data sets they hold, raising concerns about data accuracy;

- the provision of contact lists of members to social media companies without appropriate fair processing information and collation of social media with membership lists without adequate privacy assessments

The ICO issued formal warnings to 11 political parties at that time, including warning the Conservative Party about its use of people’s data.

The regulator also said it would commence audits of all 11 parties starting in January. It’s not clear how far along it’s got with that process. We’ve reached out to it with questions.

Last year the Conservative Party quietly discontinued use of a different digital campaign tool for activists, which it had licensed from a US-based add developer called uCampaign. That tool had also been used in US by Republican campaigns including Trump’s.

As we reported last year the Conservative Campaigner app, which was intended for use by party activists, linked to the developer’s own privacy policy — which included clauses granting uCampaign very liberal rights to share app users’ data, with “other organizations, groups, causes, campaigns, political organizations, and our clients that we believe have similar viewpoints, principles or objectives as us”.

Any users of the app who uploaded their phone’s address book were also handing their friends’ data straight to uCampaign to also do as it wished. A few months late, after the Conservative Campaigner app vanished from apps stores, a note was put up online claiming the company was no longer supporting clients in Europe.

0 Comments

Post a Comment